Paths to Wholeness: Fifty-Two Flower Mandalas

NOTES:

For prints of these images, please go here: http://david-bookbinder.pixels.com/collections/flower+mandalas or here: http://david-bookbinder.pixels.com/collections/flower+mandalas+white

For updates to this project, as well as new articles and images, visit flowermandalas.org and subscribe to my email list, or subscribe directly here.

UPDATES:

November 2016 UPDATE: Paths to Wholeness: Fifty-Two Flower Mandalas This month, Transformations Press is releasing a book-length collection of 52 Flower Mandala images paired with a series of related essays. Here's an endorsement and description:

David Bookbinder is one of those awakened souls whose near-death experience gave him fresh and timeless eyes. He has taken that gift and poured it into Paths to Wholeness: Fifty-Two Flower Mandalas, using innovative photography and heartfelt reflection to surface and praise the mysteries of the inner world.

– Mark Nepo, New York Times bestselling author of The Book of Awakening

– Mark Nepo, New York Times bestselling author of The Book of Awakening

Many of us long to be fully present to this amazing existence we were born into, and often we can. But sometimes, we look for help. In Paths to Wholeness: Fifty-Two Flower Mandalas, psychotherapist, writer, and photographer David J. Bookbinder brings his capacity for inspiring personal transformation to his readers. Combining words in the lineage of Carl Jung and Mark Nepo with images inspired by Georgia O’Keeffe and Harold Feinstein, David both shows and tells the tale of a spiritual seeker who, having traversed his own winding path toward awakening, now guides others to find balance, overcome fear and shame, build resilience, and to expand their hearts by listening deeply, inspiring hope, and more fully loving. Keep it by your bedside, thumb through it as you drift off to sleep, knowing you are not alone on your journey to self-actualization.

The book is available here, now: http://store.bookbaby.com/book/Paths-to-Wholeness and is available for preorders on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and other online retailers. It will ship from these sites 12/16/16.

November 2016 UPDATE: 52 (more) Flower Mandalas This month, Transformations Press is releasing a new coloring book for adults based on David's Flower Mandalas, available now on Amazon.com and soon to be released to other online retailers. The book, 52 (more) Flower Mandalas: An Adult Coloring Book for Inspiration and Stress Relief, is a collaboration between David and artist Mary O'Malley. You can find out more about Mary here: http://maryomalleyart.com. You can buy the book (a great stocking stuffer!) here: 52 (more) Flower Mandalas

November 2015 UPDATE: Coloring Book! I teamed up with illustrator Emily Sper to create a coloring book for adults from the 52 Flower Mandalas. It's been published by Diversion Publishing and is now available on Amazon: http://www.amazon.com/52-Flower-Mandalas-Coloring-Inspiration/dp/1682302016/ref=asap_bc?ie=UTF8 A sampler is available here: http://www.davidbookbinder.com/books/wp-content/uploads/sampler_52FlowerMandalas_pages.pdf

September 2014 UPDATE: Book! The book version of this project, Fifty-Two Flower Mandalas: A Meditation, has been completed, and I'm now seeking a publisher. The multimedia version will be released at the same time as book publication. Please email me at david@davidbookbinder.com if you know a publisher who might be interested in the book. Here's a preview:

I tend to work on several mandalas at once. On each piece, I spend anywhere from a few hours to a sequence of several-hour sessions spread out over a couple of months. The experience is reminiscent of meditation.

My choice of the hexagram (the Star of David, "beloved" in Hebrew) as the organizing shape for these mandalas was subconscious, but I believe this choice was no accident. In many traditions, the Star of David, composed of two overlapping triangles, represents the reconciliation of opposites male/female, fire/water, and so on. Their combination symbolizes unity and harmony. Listening to what the mandalas were telling me led me out of a dark place and, indirectly, to my decision to become a psychotherapist.

Carl Jung, one of the fathers of modern psychology, believed mandalas are a pathway to the essential Self and used them in his own personal transformation. In a small way, as both mandala artist and psychotherapist, I carry on Jung's tradition. I display several of the flower mandalas in my treatment room, and from time to time they become part of discussions with clients. The combination of natural elements and digital manipulation seems both to stimulate and to relax them.

The current selection is part of a book-in-progress. My intent is to match 52 flower mandala images with inspirational quotations and personal essays such that each image-quote-essay triplet resonates with a fundamental aspect of human experience. I intend this book to serve as a weekly meditation.

I hope publication of these images will further the process of harnessing the power of the mandala to heal.

Text and images © 2012-2015, David J. Bookbinder. All rights reserved.

Permission required for publication. Images available for licensing

davidbookbinder.com

More info on this project at Kickstarter:

http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/phototransformations/the-flower-mandalas-project

Awakening (White Rose)

If we could see the miracle of a single flower clearly, our whole life would change.

- Buddha

- Buddha

My own awakening has been slow in coming.

Much that I have learned has come from trying and failing, making wrong choices, ignoring intuition and suffering the consequences, or following it – and suffering those consequences, too. For 40 years, I have wandered, like Moses in the desert, from one occupation to another, each time getting closer, I hoped, to what I was put on the planet to do, and each time finding that the fit was not right, the path was blocked, or there was more to my nature than I had suspected. My love relationships, avocations, and spiritual path have followed a similar pattern. It has often seemed as if, like the arrow in Zeno’s Paradox, I was destined always to close the distance between where I was and where I wanted to be, with each jump forward finding that I still had half the distance to traverse, asymptotically approaching but never reaching my goal.

I would be foolish to think that now, entering my 60s, my awakening process is complete. Yet were I to have the chance to do my life over, there is little I would change. Everything has brought me to here, now – and here and now is fine.

In my late 20s I worked at the Brooklyn Museum as an instructor in a drop-in art program for kids. There, alongside children 5 to 12 years old, I discovered Chinese landscape paintings and their ethereal representations of mountains beyond mountains and rivers beyond rivers in a vast, perhaps infinite, expanse. What I think of as awakening has been like that: a journey from one layer to the next, each time aware, as I reach a marker, of the level beyond and, in the mist, the one beyond that.

My photography, and especially the Flower Mandala work, has been part of this awakening. The types of photographs I take now and the constructions I make from them allow me to re-enter the inner life of my childhood when, alienated from most of the people around me, I focused my attention on both the minuscule and the largest visible structures of the natural world. Looking deeply into what William Blake would have called the minute particulars of each image – the individual pixels, the patterns of light and shadow, positive and negative space – has helped me to understand more completely the miracle of a single flower, a tree, the line of the horizon, a moment in the life of someone I thought I knew well or someone I may never know beyond the fraction of a second when our lives intersected.

The mandala work came to me as I recovered from a medical error that culminated in a near-death experience. At that time, in 1993, I was an English graduate student at the University at Albany. My career goal then was to become a college professor and to complete a novel I planned to use as my doctoral dissertation. After some 20 years of struggling with writing as a career, I believed I was about to arrive at my right vocation and, I hoped, a happy and productive life going forward.

The near-death experience and its aftermath changed all that. To paraphrase the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia, it has been a long, strange trip.

Moments before I entered the near-death space, I envisioned a series of line charts, each layered on top of the other like the overlays of the human body in anatomy texts. The charts represented how closely I had adhered to my path. The topmost layer represented vocation. It dipped down in the bad times – the longest being my recent decade as a technical writer – and moved up in the good ones, quitting construction work or high tech and returning to graduate school. Lower layers charted additional aspects of my life: family, romantic relationships, friendships, health, . . . others I no longer recall. Each chart broke at the exact moment of the vision itself and then, after the break, resumed, the lines now moving steadily upward into the future. As I lost all bodily sensation, I felt a surge of regret for the things I might never have a chance to do. Then the regret passed and I sensed that the books of my life were balanced. I accepted that every life, no matter how short, was itself a whole, as every book in the library is a book. Yet I did not want to die. So I made a request, to God if there was one and He was listening, to let me continue. My last conscious thought: “I know how to live my life now and I’d like the chance to complete it.” Then the room and my body faded out and “I” went into another space entirely. Later, I was told my blood pressure had dropped to 50/0, but my heart continued to beat.

In 1950, Erik Erikson, one of the pioneers of developmental psychology and originator of the term “identity crisis,” posited eight ages of Man, covering human development from infancy to old age. Extending Freud’s work, he identified fundamental conflicts that each of us must resolve in order to fully actualize. If each stage’s conflict is successfully resolved, we arrive at the end of our lives with a sense of a life worth living.

Erikson identified the conflicts of the penultimate and final stages as “generativity vs stagnation” and “ego integrity vs despair.” At 61, I am nearing the end of my “generative” stage, trying to complete the work I charted in the extra time I have been granted. The near-death experience divided my life into two parts: who I had been, and who I was becoming. I have spent the last two decades integrating the two. Through this process, photography came back into my life and I returned to school yet again to become a psychotherapist. The combination of creating the images I now make and my work as a healer feels like a calling. My friend Larry, who drove me home from the hospital following my near-death experience, ends each phone or email message to me with the phrase “I hope you’re still saving the world, one person at a time.” I hope so, too.

Soon I will enter Erikson’s final stage. I have faith I will resolve that conflict successfully, arriving at my second death with wisdom and acceptance, grateful for the life I have lived and satisfied with what I have left behind, having lived authentically, eyes wide open.

Much that I have learned has come from trying and failing, making wrong choices, ignoring intuition and suffering the consequences, or following it – and suffering those consequences, too. For 40 years, I have wandered, like Moses in the desert, from one occupation to another, each time getting closer, I hoped, to what I was put on the planet to do, and each time finding that the fit was not right, the path was blocked, or there was more to my nature than I had suspected. My love relationships, avocations, and spiritual path have followed a similar pattern. It has often seemed as if, like the arrow in Zeno’s Paradox, I was destined always to close the distance between where I was and where I wanted to be, with each jump forward finding that I still had half the distance to traverse, asymptotically approaching but never reaching my goal.

I would be foolish to think that now, entering my 60s, my awakening process is complete. Yet were I to have the chance to do my life over, there is little I would change. Everything has brought me to here, now – and here and now is fine.

In my late 20s I worked at the Brooklyn Museum as an instructor in a drop-in art program for kids. There, alongside children 5 to 12 years old, I discovered Chinese landscape paintings and their ethereal representations of mountains beyond mountains and rivers beyond rivers in a vast, perhaps infinite, expanse. What I think of as awakening has been like that: a journey from one layer to the next, each time aware, as I reach a marker, of the level beyond and, in the mist, the one beyond that.

My photography, and especially the Flower Mandala work, has been part of this awakening. The types of photographs I take now and the constructions I make from them allow me to re-enter the inner life of my childhood when, alienated from most of the people around me, I focused my attention on both the minuscule and the largest visible structures of the natural world. Looking deeply into what William Blake would have called the minute particulars of each image – the individual pixels, the patterns of light and shadow, positive and negative space – has helped me to understand more completely the miracle of a single flower, a tree, the line of the horizon, a moment in the life of someone I thought I knew well or someone I may never know beyond the fraction of a second when our lives intersected.

The mandala work came to me as I recovered from a medical error that culminated in a near-death experience. At that time, in 1993, I was an English graduate student at the University at Albany. My career goal then was to become a college professor and to complete a novel I planned to use as my doctoral dissertation. After some 20 years of struggling with writing as a career, I believed I was about to arrive at my right vocation and, I hoped, a happy and productive life going forward.

The near-death experience and its aftermath changed all that. To paraphrase the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia, it has been a long, strange trip.

Moments before I entered the near-death space, I envisioned a series of line charts, each layered on top of the other like the overlays of the human body in anatomy texts. The charts represented how closely I had adhered to my path. The topmost layer represented vocation. It dipped down in the bad times – the longest being my recent decade as a technical writer – and moved up in the good ones, quitting construction work or high tech and returning to graduate school. Lower layers charted additional aspects of my life: family, romantic relationships, friendships, health, . . . others I no longer recall. Each chart broke at the exact moment of the vision itself and then, after the break, resumed, the lines now moving steadily upward into the future. As I lost all bodily sensation, I felt a surge of regret for the things I might never have a chance to do. Then the regret passed and I sensed that the books of my life were balanced. I accepted that every life, no matter how short, was itself a whole, as every book in the library is a book. Yet I did not want to die. So I made a request, to God if there was one and He was listening, to let me continue. My last conscious thought: “I know how to live my life now and I’d like the chance to complete it.” Then the room and my body faded out and “I” went into another space entirely. Later, I was told my blood pressure had dropped to 50/0, but my heart continued to beat.

In 1950, Erik Erikson, one of the pioneers of developmental psychology and originator of the term “identity crisis,” posited eight ages of Man, covering human development from infancy to old age. Extending Freud’s work, he identified fundamental conflicts that each of us must resolve in order to fully actualize. If each stage’s conflict is successfully resolved, we arrive at the end of our lives with a sense of a life worth living.

Erikson identified the conflicts of the penultimate and final stages as “generativity vs stagnation” and “ego integrity vs despair.” At 61, I am nearing the end of my “generative” stage, trying to complete the work I charted in the extra time I have been granted. The near-death experience divided my life into two parts: who I had been, and who I was becoming. I have spent the last two decades integrating the two. Through this process, photography came back into my life and I returned to school yet again to become a psychotherapist. The combination of creating the images I now make and my work as a healer feels like a calling. My friend Larry, who drove me home from the hospital following my near-death experience, ends each phone or email message to me with the phrase “I hope you’re still saving the world, one person at a time.” I hope so, too.

Soon I will enter Erikson’s final stage. I have faith I will resolve that conflict successfully, arriving at my second death with wisdom and acceptance, grateful for the life I have lived and satisfied with what I have left behind, having lived authentically, eyes wide open.

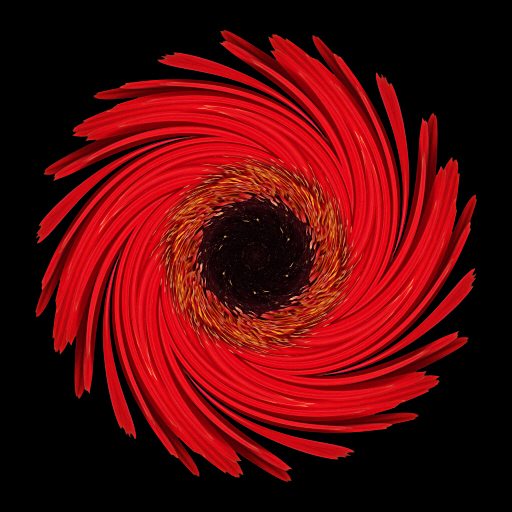

Love (Red Beach Rose)

The gaze of love is not deluded. Love sees what is best in the beloved, even when what is best in the beloved finds it hard to emerge into the light.

- J. M. Coetzee

- J. M. Coetzee

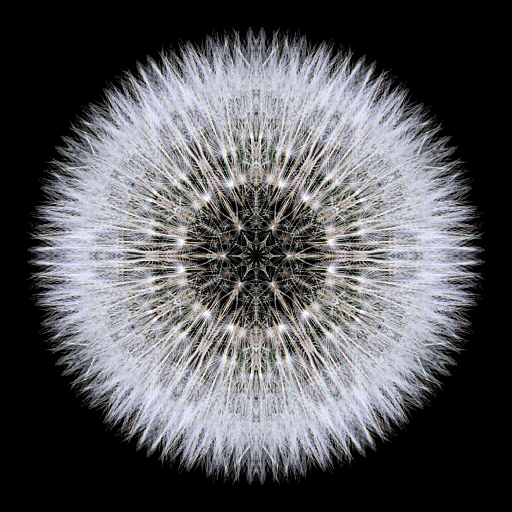

Acceptance (Dandelion Head)

It's all part of it, man.

- Jerry Garcia

- Jerry Garcia

I see Acceptance as the ability to be present as who we are, in each succession of present moments, without (as the poet John Keats put it) "irritable reaching after fact or reason." Acceptance is being swayed neither by avoiding what we fear nor clinging to what we believe we can't live without. It is seeing and embracing the ever-changing now.

Without acceptance, there can be no forward movement. Without acceptance, the hidden patterns that generate clinging attachment and fearful avoidance take over, repeating themselves in our minds, feelings, behaviors, and relationships, like a long-running Broadway play. We get caught in a whirlpool, struggling to get out without understanding that our own struggles with the here and now are only amplifying the currents that entrap us. We grow older, and the external circumstances of our lives change, but inside it's, in the words of the Talking Heads, "the same as it ever was, same as it ever was, same as it ever was."

If there is one overriding theme in what clients bring to therapy, it is that they are trapped in dysfunctional patterns. And if there is one root that factor divides clients who do not change from those do, it is acceptance: Of who they are, how they got to where they are, and that they – and only they – have the power to begin the process of freeing themselves from suffering.

Acceptance is the starting point for growth. It is the door that closes one life chapter and allows another, more liberating one, to open. Acceptance can be painful, but it is a pain that releases us from carrying our hidden burdens. Acceptance is the final stage in Elizabeth Kubler Ross’s five stages of loss and a necessary precursor to moving on from mourning. Acceptance is the first of the 12 steps in addiction recovery programs and a necessary precursor to a sober life. Acceptance of self, and of responsibility for change, is the start of true recovery from trauma, depression, addiction, anxiety, dysfunctional relationships, and the many other unhappinesses that can come our way. It is the thing most of my clients struggle hardest to avoid – and then even harder to achieve.

In its simplest form, acceptance can be saying to yourself, "Although I am suffering, I can be content now. Yes, there are things I would like to change, and when I change them I may be even more content, but I can already be content with the present circumstances, and there is much I can learn from what is occurring now." Embracing this resilient, accepting attitude can begin the shift from victim – of external circumstances, of thoughts and feelings, of physical challenges, of past injuries – to victor.

My personal pathway to acceptance has been mainly through accepting loss: lost career opportunities, lost relationships, lost health, and 20 years ago nearly the loss of my life. Getting to acceptance has come gradually, with the recognition that each loss has also been an opening. A major turning point occurred in the spring of 2007. At that time I was bleeding internally from unknown causes. By the time my doctors narrowed the source to my gastrointestinal tract, I had already lost two pints of blood. Also for unknown causes, I was rapidly losing weight, about half a pound per day. This situation, though less drastic than my experience at St. Peter’s Hospital in Albany in 1992, recalled that earlier time; I was often overcome by fear.

Over a two-week period, I underwent a series of increasingly invasive tests, but no diagnosis emerged and I continued to bleed. I am an able researcher, and I diligently scanned the Internet for information on any maladies that could explain my symptoms. I found nothing. I imagined fatal outcomes, feared the unknown.

And then one day I stopped fretting.

A Buddhist friend gave me a reading on sickness. It read:

I rely on you, Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, until I achieve enlightenment. Please grant me enough wisdom and courage to be free from delusion.

If I am supposed to get sick, let me get sick, and I'll be happy. May this sickness purify my negative karma and the sickness of all sentient beings.

If I am supposed to be healed, let all my sickness and confusion be healed, and I'll be happy. May all sentient beings be healed and filled with happiness.

If I am supposed to die, let me die, and I'll be happy. May all the delusion and the causes of suffering beings die.

If I am supposed to live a long life, let me live a long life, and I'll be happy. May my life be meaningful in service to sentient beings.

If my life is to be cut short, let it be cut short, and I'll be happy. May I and all others be free from attachment and aversion.

He instructed me to read this several times a day. At first, welcoming disease or death seemed impossible, but with each reading came a little more peace. I stopped looking things up on the Internet. I returned to my work as a therapist. I began to make art again, a practice that has, for years, been soothing and healing. I waited patiently for test results to be analyzed. And I started to have a different relationship with the passing time. Whether I would live or die, whether I would heal by myself, with major interventions, or not at all, was already out there in my future, waiting for me to arrive. I didn't have to fret. I didn't have to plan. I just had to move forward in time until my things became clear.

This was not pre-destination. This was not resignation. This was not "que sera, sera." This was something that, while I still can't fully explain it, felt like the most liberating moment in my life. It’s all already there. I don't need to fret. I don't need to push. I just need to live my life to the best of my ability and, of the infinite possible futures, I will inevitably arrive at the one that is mine.

Without acceptance, there can be no forward movement. Without acceptance, the hidden patterns that generate clinging attachment and fearful avoidance take over, repeating themselves in our minds, feelings, behaviors, and relationships, like a long-running Broadway play. We get caught in a whirlpool, struggling to get out without understanding that our own struggles with the here and now are only amplifying the currents that entrap us. We grow older, and the external circumstances of our lives change, but inside it's, in the words of the Talking Heads, "the same as it ever was, same as it ever was, same as it ever was."

If there is one overriding theme in what clients bring to therapy, it is that they are trapped in dysfunctional patterns. And if there is one root that factor divides clients who do not change from those do, it is acceptance: Of who they are, how they got to where they are, and that they – and only they – have the power to begin the process of freeing themselves from suffering.

Acceptance is the starting point for growth. It is the door that closes one life chapter and allows another, more liberating one, to open. Acceptance can be painful, but it is a pain that releases us from carrying our hidden burdens. Acceptance is the final stage in Elizabeth Kubler Ross’s five stages of loss and a necessary precursor to moving on from mourning. Acceptance is the first of the 12 steps in addiction recovery programs and a necessary precursor to a sober life. Acceptance of self, and of responsibility for change, is the start of true recovery from trauma, depression, addiction, anxiety, dysfunctional relationships, and the many other unhappinesses that can come our way. It is the thing most of my clients struggle hardest to avoid – and then even harder to achieve.

In its simplest form, acceptance can be saying to yourself, "Although I am suffering, I can be content now. Yes, there are things I would like to change, and when I change them I may be even more content, but I can already be content with the present circumstances, and there is much I can learn from what is occurring now." Embracing this resilient, accepting attitude can begin the shift from victim – of external circumstances, of thoughts and feelings, of physical challenges, of past injuries – to victor.

My personal pathway to acceptance has been mainly through accepting loss: lost career opportunities, lost relationships, lost health, and 20 years ago nearly the loss of my life. Getting to acceptance has come gradually, with the recognition that each loss has also been an opening. A major turning point occurred in the spring of 2007. At that time I was bleeding internally from unknown causes. By the time my doctors narrowed the source to my gastrointestinal tract, I had already lost two pints of blood. Also for unknown causes, I was rapidly losing weight, about half a pound per day. This situation, though less drastic than my experience at St. Peter’s Hospital in Albany in 1992, recalled that earlier time; I was often overcome by fear.

Over a two-week period, I underwent a series of increasingly invasive tests, but no diagnosis emerged and I continued to bleed. I am an able researcher, and I diligently scanned the Internet for information on any maladies that could explain my symptoms. I found nothing. I imagined fatal outcomes, feared the unknown.

And then one day I stopped fretting.

A Buddhist friend gave me a reading on sickness. It read:

I rely on you, Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, until I achieve enlightenment. Please grant me enough wisdom and courage to be free from delusion.

If I am supposed to get sick, let me get sick, and I'll be happy. May this sickness purify my negative karma and the sickness of all sentient beings.

If I am supposed to be healed, let all my sickness and confusion be healed, and I'll be happy. May all sentient beings be healed and filled with happiness.

If I am supposed to die, let me die, and I'll be happy. May all the delusion and the causes of suffering beings die.

If I am supposed to live a long life, let me live a long life, and I'll be happy. May my life be meaningful in service to sentient beings.

If my life is to be cut short, let it be cut short, and I'll be happy. May I and all others be free from attachment and aversion.

He instructed me to read this several times a day. At first, welcoming disease or death seemed impossible, but with each reading came a little more peace. I stopped looking things up on the Internet. I returned to my work as a therapist. I began to make art again, a practice that has, for years, been soothing and healing. I waited patiently for test results to be analyzed. And I started to have a different relationship with the passing time. Whether I would live or die, whether I would heal by myself, with major interventions, or not at all, was already out there in my future, waiting for me to arrive. I didn't have to fret. I didn't have to plan. I just had to move forward in time until my things became clear.

This was not pre-destination. This was not resignation. This was not "que sera, sera." This was something that, while I still can't fully explain it, felt like the most liberating moment in my life. It’s all already there. I don't need to fret. I don't need to push. I just need to live my life to the best of my ability and, of the infinite possible futures, I will inevitably arrive at the one that is mine.

Action (Blue Globe Thistle)

Actions speak louder than words.

- Unknown

The complexities of the mind and heart are endlessly fascinating, and as a therapist much can be learned from following subtle thought patterns, uncovering missing pieces of personal history, assembling it all into the Big Picture of how and why we think, feel, and do. At times I feel like a Sherlock Holmes of the mind, with each client the faithful and resourceful Watson of his or her own unsolved mystery.

A Holmes-like insight is the province of traditional psychotherapy, and it is often a helpful thing. Insight can clarify the causes of anxiety or depression, relieve guilt and shame, explicate the roots of trauma, point the way to new and better ways to live. But insight is seldom sufficient to change, and sometimes, as one of my professors, Leroy Kelley, remarked, insight is the last defense. Clients who walk out of sessions having gained another insight may feel validated and encouraged, but unless insight also leads them to act differently, stagnation often occurs.

In therapy, as in life, actions are more powerful than words. Words are frequently an important precursor to actions, but for growth to occur, we need to change not only how we think and feel, but also what we do. Identifying dysfunctional patterns, self-sabotaging thoughts, and triggered feelings that keep us prisoners of our problems is an important, even vital, preparatory step to change, but it is never enough.

My former therapist and mentor, Jim Grant, envisions our collections of patterned thoughts, feelings, and behaviors as akin to a magic spell that leads us to act in ritualized, self-sabotaging ways. To break the spell, we need not only to alter our thoughts and feelings, but also our actions. Even a slight change in behavior introduces something new and opens the way for future change that no amount of additional insight can, by itself, create.

Addiction is a clear-cut example of spell-mediated, patterned behavior. Addicts typically follow a small set of addiction-spell commands that perpetuate the addictive behavior, such as:

· "Once I get the idea in my head, I have to get high."

· "I'd like to stop but quitting is too hard."

· "If I'm around it I have to do it."

· "Getting high is the only thing I have to look forward to."

· "Once I get the idea in my head, I have to get high."

· "I'd like to stop but quitting is too hard."

· "If I'm around it I have to do it."

· "Getting high is the only thing I have to look forward to."

In therapy, addict clients can learn to identify triggers, deconstruct their addiction spell commands, and work through the feelings and experiences that led them into addiction. All of this helps. But to break the addiction cycle, they also have to act differently. They have to change their relationships to friends and families, employment, community. They must learn to do new things when they want to get high and have the will to avoid situations that tempt them to use. In the beginning of their spell-breaking journey, they have to act as if they are through with addiction, "faking it till they make it," even when every conscious thought and habituated feeling is screaming to them to use. Like Odysseus navigating between Scylla and Charybdis, they must tie themselves to the mast of sobriety and resist the sirens' song. They must, to paraphrase Eleanor Roosevelt, do the thing they think they cannot do.

What is true for addiction applies to any of the mental maladies that bring people to therapy. Each client has his or her own patterns of thought, feeling, and behavior, and each requires not just insights - words - but also actions to break the cycle and create new, more fulfilling ways to be in the world.

I have been drawn to schools of therapy that encourage both words and actions. Solution-Focused therapy uses words to help clients envision their desired life, but change happens only when they tackle weekly challenges that move them, baby step by baby step, toward their goals. Focusing-Oriented therapy uses words to help clients tap into segmented parts of themselves and to discover what these fragments of self need in order to rejoin the whole, but each session ends with an action item, a step in the right direction. Gestalt Therapy, which melds psychodrama and Gestalt philosophy, emphasizes awareness to help clients understand the beliefs and habits that govern their lives, but it also incorporates "experiments" that change behavior in the session itself, empowering them to take these changes out into the world.

I use these and other spell-breaking modalities in my sessions with clients. But spell-breaking is not limited to psychotherapy. All that is needed is a practice that allows us to recognize that our self-defeating patterns exist, to identify what they want us to do, and to choose, through whatever means available to us, to do otherwise.

I frequently give this short poem by Portia Nelson, "An Autobiography in Five Short Chapters," to clients to encourage them to act differently. Maybe you, too, will find it helpful.

I frequently give this short poem by Portia Nelson, "An Autobiography in Five Short Chapters," to clients to encourage them to act differently. Maybe you, too, will find it helpful.

I have.

I walk down the street.

There is a deep hole in the sidewalk.

I fall in.

I am lost... I am hopeless.

It isn't my fault.

It takes forever to find a way out.

I walk down the same street.

There is a deep hole in the sidewalk.

I pretend I don't see it.

I fall in again.

I can't believe I am in this same place.

But it isn't my fault.

It still takes a long time to get out.

I walk down the same street.

There is a deep hole in the sidewalk.

I see it there.

I still fall in... it's a habit... but,

my eyes are open.

I know where I am.

It is my fault.

I get out immediately.

I walk down the same street.

There is a deep hole in the sidewalk.

I walk around it.

I walk down another street

Anger (Pale Yellow Gerbera Daisy)

Treat your anger with the utmost respect and tenderness, for it is no other than yourself.

-Thich Nhat Hanh

-Thich Nhat Hanh

ANGER: HEAVEN AND HELL

As I emerged from a childhood depression, the first true emotion I felt as a young teenager was Anger. I remember listening to Jimmy Hendrix, loud, a foot away from the speakers so the music rocked my entire body. I remember breaking and tearing things in secret. I remember feeling almost grateful for the Vietnam War because it gave me something legitimate to focus my anger on. Anger was energy, and at that time it may even have been life-saving energy, though looking back I see that it was also imprisoning.

That is the nature of anger. “You will not be punished for your anger,” the Buddha once wrote. “You will be punished by your anger.”

Directly acting out anger is usually destructive. Many of the clients I see act out anger in an attempt to “make the other person feel the way I do.” Even if they accomplish that goal, the mutual understanding they implicitly hope for is seldom, if ever, achieved. Instead, they have an escalating, mutually damaging battle. In psychotherapy settings, various forms of reenacting anger are frequently promoted as beneficial alternatives. In the movie Analyze This, Billy Crystal and Robert De Niro parody therapeutic anger reenactment. Crystal’s character, a psychiatrist, tells De Niro’s, his mobster patient, to “just hit the pillow” when he’s angry. De Niro promptly pulls out his pistol and fires several rounds into Crystal’s office chair. Crystal pauses for a moment, smiles uneasily, then asks, “Feel better?” De Niro shrugs. “Yeah, I do,” he says.

Hitting the pillow is preferable to hitting a person. But even in comedy, it takes more – and less – than that to truly resolve anger. Acting out, venting, and similar ways to “let off steam” sometimes do make us feel momentarily better. More often, they merely amplify the anger and create further barriers to resolving it.

Suppression – holding anger in, “biting your tongue,” “sucking it up” – also has its costs. Anger turned inward long enough leads to depression, injures the body, builds defensive walls between people, promotes passive-aggressive acting out, or surfaces explosively elsewhere, finding an exit like magma in a volcanic eruption.

If we can’t act on anger directly, act it out symbolically, or suppress it without creating further harm, then what is to be done to resolve it?

From Vietnamese Buddhist master Thich Nhat Hanh, I have been learning to relate to anger as if it were a baby in distress, crying for attention. Once I asked one of my young clients, an eight-year-old boy frequently overcome with rage at his teacher, how he would treat this anger if it were a real baby crying. “I’d pick it up and see if it wanted to be held.” And if it still cried? “I’d try giving it a bottle.” And if that didn’t work? “I’d see if it had a poopy diaper.” To deal well with our anger, we need to find out if it needs to be held, needs to be fed. Or has a poopy diaper. Then we need to give it the attention it requires. Only then can we safely bring our grievances to those we are angry with.

In Thich Nhat Hanh’s community in France, members make peace treaties. When they are angry, they agree to let the person they are angry with know about the anger and ask for their help. Within 24 hours, they will meet to try to resolve the conflict. In the meantime, each person commits to working through what baggage he or she has brought to the conflict, so that when they do come together, only the actual issues between them remain. If one or the other is still in a triggered state when they meet, they reschedule, resume caring for the crying baby, and try again within another 24 hours. Sometimes the issues that still remain are hard to work through. But often, resolution is as simple as clearing up misunderstanding and rendering an apology for unintended suffering. People who work with anger in this way have a collaborative peace process instead of an escalating battle nobody can win.

In my therapy practice, I condense the peace process using a technique borrowed from the writings of Harville Hendrix, a well-known couples counselor. At the beginning of a couples or parent/child session, I explain that in this conversation each person will have a chance to fully state his or her grievance: one will speak while the other listens actively, and then they will reverse roles. Next, I ask the listener to get into a state of openness to prepare for taking in what the speaker says without reacting, withdrawing, disagreeing, or defending, even when something feels hurtful or sounds “wrong.”

Then the speaker speaks. Sometimes there is recollection of a longstanding pattern of dissatisfaction. Sometimes old injuries, never healed, are brought forth. Sometimes an argument that took place in the car on the way to therapy, or in the waiting room, continues. As the speaker tells his or her story, the listener mirrors it back, one manageable chunk at a time, checking to make sure he or she got it. The speaker continues the narrative only when each chunk is fully understood. This speaking/listening/mirroring/validation process continues until all the important parts of the story have been heard and understood.

Finally, the listener summarizes it all, making a kind of intellectual sense of it. “So, now that I hear how you experienced what I did or said, I can understand why you are angry.” If possible, the listener also empathizes. “Putting myself in your shoes, I would be angry, too.” Knowing that they will soon have an opportunity to present their points of view, listeners feel freer to respond with compassion. Often an apology follows. “I am sorry that what I said and did hurt you. I didn’t mean for things to happen this way. I don’t want to cause you pain.” Tears sometimes come. Something has shifted.

After the speaker has been heard, understood, and empathized with, it is his or her turn to actively listen. The process concludes when each party has been both speaker and listener.

The mutual understanding and caring encouraged by this process starts the building of a solid base for conflict resolution. Over time, practicing the peace treaty and active, empathic listening creates a durable relationship container that can hold the sometimes violent feelings that occur between people.

Similar techniques of conflict resolution have been used by pioneer psychotherapist Carl Rogers, by founder of the Center for Nonviolent Communication Marshall B. Rosenberg, and by many others. They are practiced in counseling settings, but also in areas of great historical conflict such as the Middle East, Latin America, and Ireland, with the result that although some racial or political hatred may remain, the participants see each other as individuals suffering just as they have suffered. Again, something has shifted.

Anger can feel empowering. But its resolution is a liberation. Author Ken Feit illustrates the difference with this story. “Once a samurai warrior went to a monastery and asked a monk, ‘Can you tell me about heaven and hell?’ The monk answered, ‘I cannot tell you about heaven and hell. You are much too stupid.’ The warrior’s face became contorted with rage. ‘Besides that,’ continued the monk, ‘you are very ugly.’ The warrior gave a scream and raised his sword to strike the monk. ‘That,’ said the monk unflinchingly, ‘is hell.’ The samurai slowly lowered his sword and bowed his head. ‘And that,’ said the monk, ‘is heaven.’”

As I emerged from a childhood depression, the first true emotion I felt as a young teenager was Anger. I remember listening to Jimmy Hendrix, loud, a foot away from the speakers so the music rocked my entire body. I remember breaking and tearing things in secret. I remember feeling almost grateful for the Vietnam War because it gave me something legitimate to focus my anger on. Anger was energy, and at that time it may even have been life-saving energy, though looking back I see that it was also imprisoning.

That is the nature of anger. “You will not be punished for your anger,” the Buddha once wrote. “You will be punished by your anger.”

Directly acting out anger is usually destructive. Many of the clients I see act out anger in an attempt to “make the other person feel the way I do.” Even if they accomplish that goal, the mutual understanding they implicitly hope for is seldom, if ever, achieved. Instead, they have an escalating, mutually damaging battle. In psychotherapy settings, various forms of reenacting anger are frequently promoted as beneficial alternatives. In the movie Analyze This, Billy Crystal and Robert De Niro parody therapeutic anger reenactment. Crystal’s character, a psychiatrist, tells De Niro’s, his mobster patient, to “just hit the pillow” when he’s angry. De Niro promptly pulls out his pistol and fires several rounds into Crystal’s office chair. Crystal pauses for a moment, smiles uneasily, then asks, “Feel better?” De Niro shrugs. “Yeah, I do,” he says.

Hitting the pillow is preferable to hitting a person. But even in comedy, it takes more – and less – than that to truly resolve anger. Acting out, venting, and similar ways to “let off steam” sometimes do make us feel momentarily better. More often, they merely amplify the anger and create further barriers to resolving it.

Suppression – holding anger in, “biting your tongue,” “sucking it up” – also has its costs. Anger turned inward long enough leads to depression, injures the body, builds defensive walls between people, promotes passive-aggressive acting out, or surfaces explosively elsewhere, finding an exit like magma in a volcanic eruption.

If we can’t act on anger directly, act it out symbolically, or suppress it without creating further harm, then what is to be done to resolve it?

From Vietnamese Buddhist master Thich Nhat Hanh, I have been learning to relate to anger as if it were a baby in distress, crying for attention. Once I asked one of my young clients, an eight-year-old boy frequently overcome with rage at his teacher, how he would treat this anger if it were a real baby crying. “I’d pick it up and see if it wanted to be held.” And if it still cried? “I’d try giving it a bottle.” And if that didn’t work? “I’d see if it had a poopy diaper.” To deal well with our anger, we need to find out if it needs to be held, needs to be fed. Or has a poopy diaper. Then we need to give it the attention it requires. Only then can we safely bring our grievances to those we are angry with.

In Thich Nhat Hanh’s community in France, members make peace treaties. When they are angry, they agree to let the person they are angry with know about the anger and ask for their help. Within 24 hours, they will meet to try to resolve the conflict. In the meantime, each person commits to working through what baggage he or she has brought to the conflict, so that when they do come together, only the actual issues between them remain. If one or the other is still in a triggered state when they meet, they reschedule, resume caring for the crying baby, and try again within another 24 hours. Sometimes the issues that still remain are hard to work through. But often, resolution is as simple as clearing up misunderstanding and rendering an apology for unintended suffering. People who work with anger in this way have a collaborative peace process instead of an escalating battle nobody can win.

In my therapy practice, I condense the peace process using a technique borrowed from the writings of Harville Hendrix, a well-known couples counselor. At the beginning of a couples or parent/child session, I explain that in this conversation each person will have a chance to fully state his or her grievance: one will speak while the other listens actively, and then they will reverse roles. Next, I ask the listener to get into a state of openness to prepare for taking in what the speaker says without reacting, withdrawing, disagreeing, or defending, even when something feels hurtful or sounds “wrong.”

Then the speaker speaks. Sometimes there is recollection of a longstanding pattern of dissatisfaction. Sometimes old injuries, never healed, are brought forth. Sometimes an argument that took place in the car on the way to therapy, or in the waiting room, continues. As the speaker tells his or her story, the listener mirrors it back, one manageable chunk at a time, checking to make sure he or she got it. The speaker continues the narrative only when each chunk is fully understood. This speaking/listening/mirroring/validation process continues until all the important parts of the story have been heard and understood.

Finally, the listener summarizes it all, making a kind of intellectual sense of it. “So, now that I hear how you experienced what I did or said, I can understand why you are angry.” If possible, the listener also empathizes. “Putting myself in your shoes, I would be angry, too.” Knowing that they will soon have an opportunity to present their points of view, listeners feel freer to respond with compassion. Often an apology follows. “I am sorry that what I said and did hurt you. I didn’t mean for things to happen this way. I don’t want to cause you pain.” Tears sometimes come. Something has shifted.

After the speaker has been heard, understood, and empathized with, it is his or her turn to actively listen. The process concludes when each party has been both speaker and listener.

The mutual understanding and caring encouraged by this process starts the building of a solid base for conflict resolution. Over time, practicing the peace treaty and active, empathic listening creates a durable relationship container that can hold the sometimes violent feelings that occur between people.

Similar techniques of conflict resolution have been used by pioneer psychotherapist Carl Rogers, by founder of the Center for Nonviolent Communication Marshall B. Rosenberg, and by many others. They are practiced in counseling settings, but also in areas of great historical conflict such as the Middle East, Latin America, and Ireland, with the result that although some racial or political hatred may remain, the participants see each other as individuals suffering just as they have suffered. Again, something has shifted.

Anger can feel empowering. But its resolution is a liberation. Author Ken Feit illustrates the difference with this story. “Once a samurai warrior went to a monastery and asked a monk, ‘Can you tell me about heaven and hell?’ The monk answered, ‘I cannot tell you about heaven and hell. You are much too stupid.’ The warrior’s face became contorted with rage. ‘Besides that,’ continued the monk, ‘you are very ugly.’ The warrior gave a scream and raised his sword to strike the monk. ‘That,’ said the monk unflinchingly, ‘is hell.’ The samurai slowly lowered his sword and bowed his head. ‘And that,’ said the monk, ‘is heaven.’”

Apology (Pale Yellow Daffodil)

Apology doesn't change the past, but it widens the future.

- Unknown

- Unknown

APOLOGY: MENDING THE RIFT

Prior to undertaking therapist training, I took a short course in community mediation. Most of my mediation experience was as a volunteer in small claims court. We mediators helped conflicting parties try to reach a mutually satisfying agreement rather than simply letting a judge adjudicate the case.

Small claims court is all about settling financial arguments, and money was always the identified issue in the cases we handled. But in mediation, a strange thing happened: almost always, it turned out that what the aggrieved party most needed was a heartfelt apology and a way to remedy their grievance. When the apology came – and it did, often – the agreement quickly followed. The change in demeanor from start to finish could be dramatic: I remember one case where two women, a homeowner and a landscaping contractor, began in bitter conflict but walked out with their arms around each other, sharing tears.

Something similar happens in couples counseling. Couples often come to therapy as a last resort, with histories of conflict that make reconciliation seem impossible even to me. But when both sides put all their cards on the table in a clear, non-blaming way, so they can finally understand the effect they have had on each other, apologies almost always come, and with them, a positive shift in the relationship. The pattern of mutual understanding leading to apology and reconciliation also occurs with addict clients and their families. I see this pattern play out in family therapy, too. In both instances, the “identified problem” client, once fully understood by his or her family, typically leaves therapy having both rendered and received an apology, and with it a new family dynamic begins.

The first step to reconciliation is almost always an apology for the suffering we have caused, even if unintentionally. The next is to agree to make amends for any harm done, whenever doing so creates no further harm. This sequence is well established in twelve-step recovery programs. It seems less well understood, however, by the rest of us. In Western culture, we seem to fear apology. Apologizing seems shameful, excessively humbling, or an admission of wrongdoing, so we avoid it. Instead, what most of us do, when someone has charged us with wronging, is one or more of the following:

These strategies usually escalate conflict rather than resolving it. When we believe someone has done us wrong, we are not customers for denial, counter-accusations, or even explanations. We want our injured feelings and our view of events understood and validated, and we want the person we believe has harmed us to express sorrow for our suffering. Once that occurs and an apology is offered and accepted, healing the rift can begin.

Apology is a turning point in conflict resolution and also a prime example of “better late than never.” Apologies can come at any time, even decades later, and still have their healing effect. Two personal examples: Had the Albany surgeon and gastroenterologist who nearly killed me apologized for their errors in judgement, I would have worked with them to rectify the harm done rather than suing them for damages. When, at age 70, my mother apologized for mistakes she had made with me as child, my heart opened, and it has remained open; where previously, for some 25 years, most of our interactions were either guarded or hostile, now we freely express our mutual love.

Apologizing well, like any other skill, requires practice and attention, but it is worth getting it right. The key to apology is that we need to practice it not only when we have knowingly done harm, but also when the suffering is due to inadvertent actions, misunderstanding, or misinterpretation – whenever our actions have resulted in suffering. To apologize for suffering is not to admit wrongdoing, but instead to declare that whatever the cause, we want to rectify the harm done and mend the rift that has occurred. By apologizing, we stop the cycle of attack and counterattack, and open the path to forgiveness, reconciliation, and trust.

Prior to undertaking therapist training, I took a short course in community mediation. Most of my mediation experience was as a volunteer in small claims court. We mediators helped conflicting parties try to reach a mutually satisfying agreement rather than simply letting a judge adjudicate the case.

Small claims court is all about settling financial arguments, and money was always the identified issue in the cases we handled. But in mediation, a strange thing happened: almost always, it turned out that what the aggrieved party most needed was a heartfelt apology and a way to remedy their grievance. When the apology came – and it did, often – the agreement quickly followed. The change in demeanor from start to finish could be dramatic: I remember one case where two women, a homeowner and a landscaping contractor, began in bitter conflict but walked out with their arms around each other, sharing tears.

Something similar happens in couples counseling. Couples often come to therapy as a last resort, with histories of conflict that make reconciliation seem impossible even to me. But when both sides put all their cards on the table in a clear, non-blaming way, so they can finally understand the effect they have had on each other, apologies almost always come, and with them, a positive shift in the relationship. The pattern of mutual understanding leading to apology and reconciliation also occurs with addict clients and their families. I see this pattern play out in family therapy, too. In both instances, the “identified problem” client, once fully understood by his or her family, typically leaves therapy having both rendered and received an apology, and with it a new family dynamic begins.

The first step to reconciliation is almost always an apology for the suffering we have caused, even if unintentionally. The next is to agree to make amends for any harm done, whenever doing so creates no further harm. This sequence is well established in twelve-step recovery programs. It seems less well understood, however, by the rest of us. In Western culture, we seem to fear apology. Apologizing seems shameful, excessively humbling, or an admission of wrongdoing, so we avoid it. Instead, what most of us do, when someone has charged us with wronging, is one or more of the following:

These strategies usually escalate conflict rather than resolving it. When we believe someone has done us wrong, we are not customers for denial, counter-accusations, or even explanations. We want our injured feelings and our view of events understood and validated, and we want the person we believe has harmed us to express sorrow for our suffering. Once that occurs and an apology is offered and accepted, healing the rift can begin.

Apology is a turning point in conflict resolution and also a prime example of “better late than never.” Apologies can come at any time, even decades later, and still have their healing effect. Two personal examples: Had the Albany surgeon and gastroenterologist who nearly killed me apologized for their errors in judgement, I would have worked with them to rectify the harm done rather than suing them for damages. When, at age 70, my mother apologized for mistakes she had made with me as child, my heart opened, and it has remained open; where previously, for some 25 years, most of our interactions were either guarded or hostile, now we freely express our mutual love.

Apologizing well, like any other skill, requires practice and attention, but it is worth getting it right. The key to apology is that we need to practice it not only when we have knowingly done harm, but also when the suffering is due to inadvertent actions, misunderstanding, or misinterpretation – whenever our actions have resulted in suffering. To apologize for suffering is not to admit wrongdoing, but instead to declare that whatever the cause, we want to rectify the harm done and mend the rift that has occurred. By apologizing, we stop the cycle of attack and counterattack, and open the path to forgiveness, reconciliation, and trust.

Atonement (Iceland Poppy)

The beginning of atonement is the sense of its necessity.

- Lord Byron

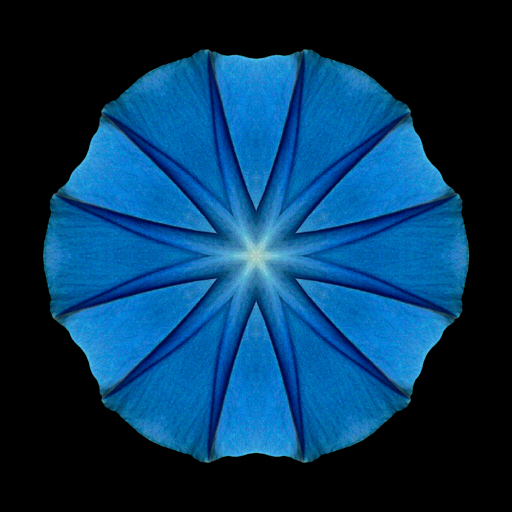

Grace (Blue Morning Glory)

Grace is given not because we have done good works, but in order that we may be able to do them.

- Saint Augustine of Hippo

- Saint Augustine of Hippo

Compassion (White Daffodil)

Until he extends his circle of compassion to include all living things, man will not himself find peace.

- Albert Schweitzer

- Albert Schweitzer

Change (Dying Amaryllis)

No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it's not the same river and he's not the same man.

- Heraclitis of Ephesus

- Heraclitis of Ephesus

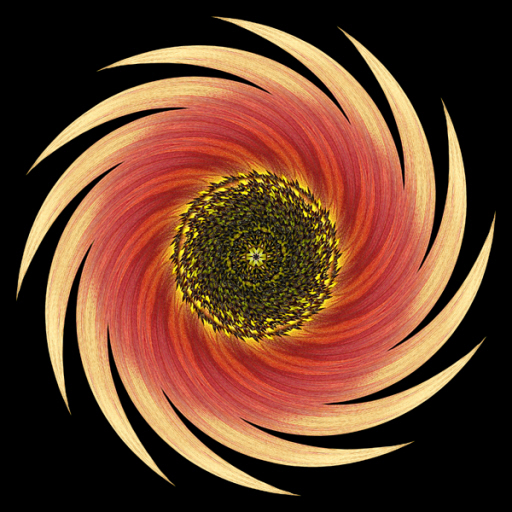

Sunflower 'Moulin Rouge' (Change) [Alternate]

You must be the change you want to see in the world.

- Mahatma Gandhi

Passion (Pink Peony)

Be still when you have nothing to say; when genuine passion moves you, say what you've got to say, and say it hot.

- D H Lawrence

- D H Lawrence

Choice (White Lily)

It’s choice – not chance – that determines your destiny.

- Jean Nidetch

Balance (Deep Orange Marigold)

You can’t have a light without a dark to stick it in.

- Arlo Guthrie

Stillness (Water Lily)

In the midst of movement and chaos, keep stillness inside of you.

- Deepak Chopra

Self Love (Pink Dahlia)

You, yourself, as much as anybody in the entire universe, deserve your love and affection.

- Buddha

- Buddha

Boldness (Light Red Zinnia Elegans)

Be bold -- and mighty forces will come to your aid.

- Basil King

- Basil King

Hope (White and Yellow Daffodil)

"Hope" is the thing with feathers

That perches in the soul

And sings the tune without the words

...And never stops at all

And sweetest in the Gale is heard

And sore must be the storm

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm

I've heard it in the chillest land

And on the strangest Sea

Yet, never, in Extremity,

It asked a crumb of Me.

- Emily Dickinson

That perches in the soul

And sings the tune without the words

...And never stops at all

And sweetest in the Gale is heard

And sore must be the storm

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm

I've heard it in the chillest land

And on the strangest Sea

Yet, never, in Extremity,

It asked a crumb of Me.

- Emily Dickinson

Perfection (Violet Cosmos)

The Perfect is the enemy of the Good.

- Voltaire

- Voltaire

Listening (Rudbeckia 'Prairie Sun')

The first duty of love is to listen.

- Paul Tillich

Humor (Violet Zinnia Elegans)

When humor goes, there goes civilization.

Erma Bombeck

Patience (White Cosmos)

Patience is also a form of action.

Auguste Rodin

Awareness (Yellow Sunflower)

Nobody sees a flower – really – it is so small – we haven’t time – and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time.

Georgia O'Keeffe